The Romans did not number each day of a month from the first to the last day. Instead, they counted back from three fixed points of the month: the Nones (the 5th or 7th, nine days inclusive before the Ides), the Ides (the 13th for most months, but the 15th in March, May, July, and October), and the Kalends (1st of the following month). Originally the Ides were supposed to be determined by the full moon, reflecting the lunar origin of the Roman calendar. In the earliest calendar, the Ides of March would have been the first full moon of the new year.

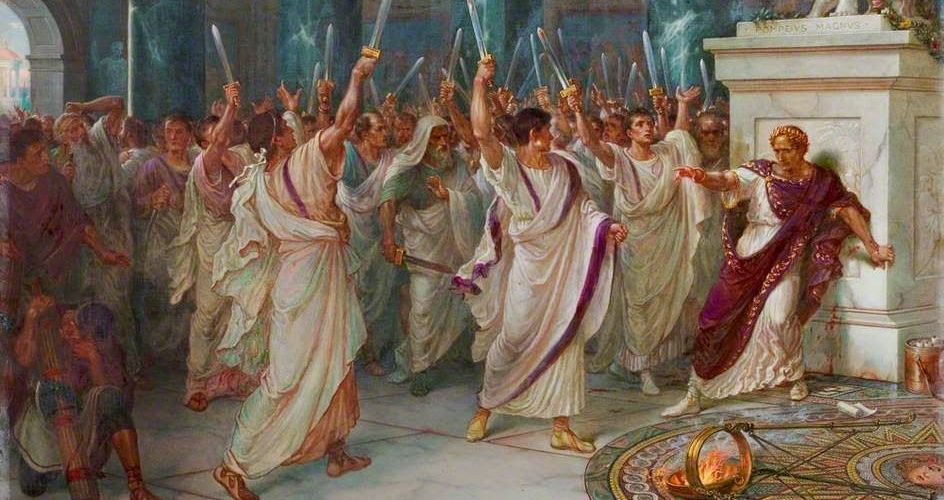

Assassination of Caesar

In modern times, the Ides of March is best known as the date on which Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. Caesar was stabbed to death at a meeting of the Senate. As many as 60 conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius, were involved. According to Plutarch, a seer had warned that harm would come to Caesar on the Ides of March. On his way to the Theatre of Pompey, where he would be assassinated, Caesar passed the seer and joked, “Well, the Ides of March come”, implying that the prophecy had not been fulfilled, to which the seer replied, “Aye, they come, but they are not gone.” This meeting is famously dramatized in William Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar when Caesar is warned by the soothsayer to “beware the Ides of March.” The Roman biographer Suetonius identifies the “seer” as a haruspex named Spurinna.

Caesar’s death was a closing event in the crisis of the Roman Republic and triggered the civil war that would result in the rise to sole power of his adopted heir Octavian (later known as Augustus). Writing under Augustus, Ovid portrays the murder as a sacrilege, since Caesar was also the Pontifex Maximus of Rome and a priest of Vesta. On the fourth anniversary of Caesar’s death in 40 BC, after achieving a victory at the siege of Perugia, Octavian executed 300 senators and equities who had fought against him under Lucius Antonius, the brother of Mark Antony. The executions were one of a series of actions taken by Octavian to avenge Caesar’s death. Suetonius and the historian Cassius Dio characterized the slaughter as a religious sacrifice, noting that it occurred on the Ides of March at the new altar to the deified Julius.

Don’t Beware

You’ve probably heard the soothsayer’s warning to Julius Caesar in William Shakespeare’s play of the same name: “Beware the Ides of March.” Not only did Shakespeare’s words stick, but they also branded the phrase—and the date, March 15—with a dark and gloomy connotation. Likely, many people who use the phrase today don’t know its true origin. Just about every pop culture reference to the Ides—save for those appearing in actual history-based books, movies, or television specials—makes it seem like the day itself is cursed.

Did the death of Caesar curse the day, or was it just Shakespeare’s mastery of language that forever darkened an otherwise normal box on the calendar? If you look through history, you can certainly find enough horrible things that happened on March 15, but is it a case of life imitating art? Or art imitating life?

Perhaps it was Julius Caesar himself (and not the famous playwright) who caused all the drama. After all, he’s the one who uprooted Rome’s New Year celebration from their traditional March 15 date to January…just two years before he was betrayed and butchered by members of the Roman senate.

Written By:

Sohaib Ali Afzal